"Plain English" is like no other programming language I've ever seen. Unlike

the many "write only" languages (which you can learn to write, but are very

difficult to read and understand) this seems to be a "read only" language.

I find it stunningly easy to read and understand, but rather difficult to

write anything in. You think you know how to program in "Plain English" because you can speak plain English, but "Plain English" doesn't actually understand plain English. I think a non-programmer might find it easier to learn.

My brain is rather "infected" with C. And Javascript.

Here is a list of what you must understand from the start:

-

Fully Implemented in Itself: It is a single executable, with one or

more human readable libraries (also written in Plain English) which produces

a new stand alone .exe with your new program in it. It is NOT a compiler

only that takes in source and produces compiled code. It is NOT an IDE only,

that shells out to a compiler. It is both. There is NO complete source code

in another language; the system was bootstrapped in a language which

is no longer available and was later re-written entirely in Plain English.

-

It is "Machine Code" Low Level: The bootstrap is very basic, only

able to copy itself and add raw machine code in Intel hex format, make calls

to the operating system, e.g.

Call "kernel32.dll" "SetFilePointer" with the file and 0 and 0 and 2

[file_end] returning a result number.

and call other DLLs e.g.

Call "hawk.dll" "Servo_SetServos" with 1 and the front knob's setting

and the side knob's setting and 0 and 0 and 0 and 0 and 0 and 0 returning

a number.

and it can do a few other things.

-

It is "English" High Level: From those humble beginnings, springs

a language that can do things like:

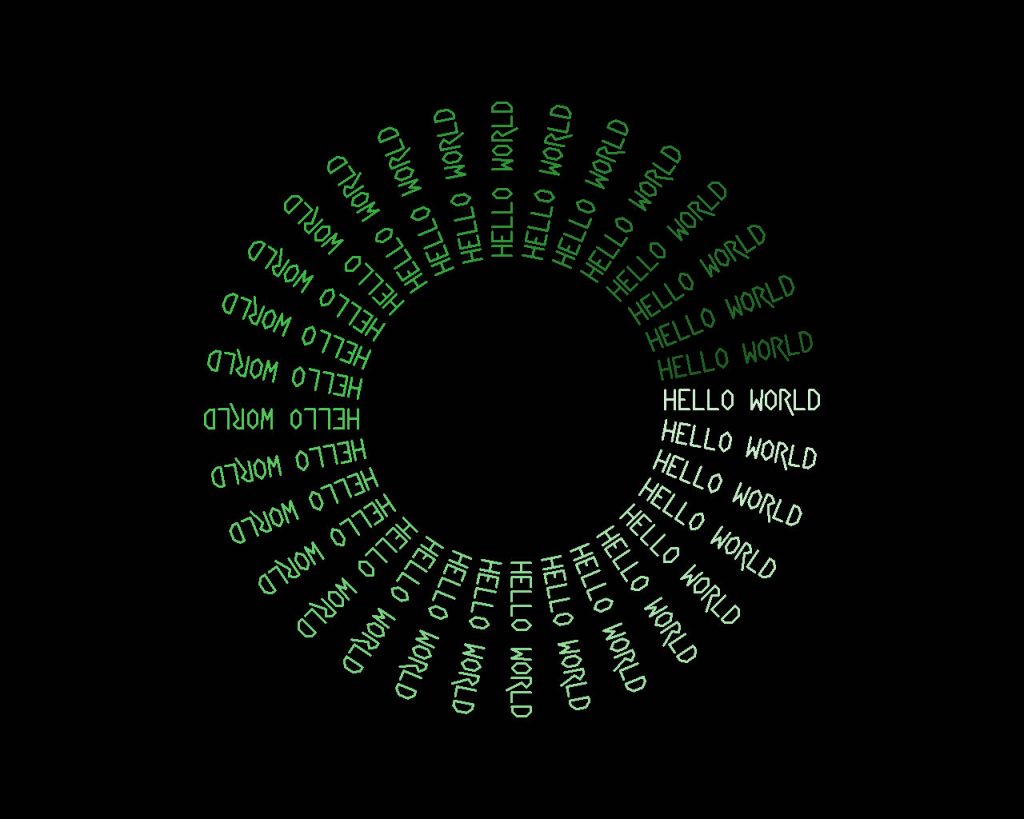

To run:

Start up.

Clear the screen.

Use medium letters. Use the fat pen.

Pick a really dark color.

Loop.

Start in the center of the screen.

Turn left 1/32 of the way.

Turn right. Move 2 inches. Turn left.

Write "HELLO WORLD".

Refresh the screen.

Lighten the current color about 20 percent.

Add 1 to a count. If the count is 32, break.

Repeat.

Wait for the escape key.

Shut down.

Note that standard English punctuation, word types, and sentence structure

are all used. There is a trend to make each sentence is own paragraph, but

that is not required.

-

Compact: The entire download is less than a megabyte in size.

"But it's a complete development environment, including a unique interface,

a simplified file manager, an elegant text editor, a handy hexadecimal dumper,

a native-code-generating compiler/linker, a library of general-purpose types,

variables and routines, and even a wysiwyg page layout facility (that we

used to produce the documentation). It is written entirely in Plain English.

The source code (about 25,000 sentences) is included in the download." All

the commands are hidden in the alphabet along the top of the IDE. E.g. to

close a folder, after clicking on a drive letter and folder, click "C" and

then "Close", or use the Alt- hot-keys like Alt-C. I found that VERY confusing

to start, but it makes sense now and is another example of compactness as

it supports a massive menu structure with 26 icons.

Types

Primitive types like number, etc.. are supported, as well as more complex

types like "thing" which is a sort of object or list, and any number of

user-defined types. Note however that "number" is a 32 bit integer and is

/directly/ mapped to the CPU. E.g. addition is literally this in the language:

To add a number to another number:

Intel $8B85080000008B008B9D0C0000000103.

And yes, that is 80x86 machine code in Intel hex format. It decompiles to

mov eax, [ebp+8] ;load the current stack address + 8 into the accumulator

mov eax, [eax] ;load memory pointed to by accumulator into accumulator

mov ebx, [ebp+12] ;load the current stack address + 12 into working register

add [ebx],eax ;add accumulator to memory pointed to by working register

So the language has stacked pointers (all parameters are passed by reference)

to the two numbers via a number to another number and then it calls

this code which gets the first number, and adds it to the second. Hopefully

this example shows how high level and low level Plain English is at the same

time.

"The whole system is built on just two, compiler-defined types: BYTE and

RECORD. All the other types are constructed from these, and are defined in

the "Noodle" library {a file, loaded by the compiler}. The idea was to put

as much as we could in the library, and as little as possible in the compiler.

The compiler is aware of a few other types -- like NUMBER, STRING, SUBSTRING,

THING -- mostly for memory management purposes, but all the other the type

definitions are built up from BYTE and RECORD in the library." These are

extended to support BYTE, WYRD, POINTER, FLAG, and RECORD.

Subset types give new names to existing types: e.g.

A count is a number.

A name is a string.

Constants or "literals" are also possible:

The copyright byte is a byte equal to 169.

As are conversion types:

A foot is 12 inches.

An hour is 60 minutes.

Variables

Once a type has been declared, we can allocate a global, outside a routine

The great foo is a number.

then values may be assigned, inside a routine

Put 0 into the great foo

or be passed by address...

Increment the great foo.

as a parameter to a routine.

To increment a number:

Add 1 to the number.

Note that variables can have multi-word names including spaces.

Local variables, with scope in their own routine only, are defined so

simply they can be hard to see. Basically, you assign a value using

an indefinite article (A, AN, ANOTHER, or SOME) in a statement. For

example:

Put 101 into some other course number.

The local variable name there is "other course number" but "other course"

also works as a "nickname". The variable's type is number.

e.g.

Increment the other course.

will match To increment a number:

"All parameters passed to Plain English routines are passed by reference,

though parameters passed to DLLs use the C convention (the order is reversed

and "simple" types are passed by value)."

Routines

Routines are defined by headers which terminate in a colon, followed by the

body of the routine. Multiple headers can be provided in front of one routine,

separated by semicolons:

To add a number to a count;

To increment a number by a count:

The language parses these into Monikettes: (1) add (2) [number] (3) in/into/to

(4) [count] which, taken together make up the routines Moniker: add

[number] in/into/to [count]

Matching procedure definitions to procedure calls is done in stages.

1. Higher-level types are reduced to compatible lower-level types, as necessary;

and

2. Certain less-essential words are considered equivalent.

For example, the compiler will match this imperative sentence: Write

the first name using the blue pen. with this routine header To write

a string with a color: even though the source types "name" and "pen"

are different (but compatible) with the target types "string" and "color",

and even though the source preposition "using" is different than the target

preposition "with".

Unless, of course, a more exact match is available, such as:

To write a name from/given/with/using a pen:

To write a name from/given/with/using a color:

To write a string from/given/with/using a pen:

Type reductions proceed, recursively, from left to right, until a match is

found (or all combinations have failed, which results in a compile-time error).

Decider: A type of routine which helps TO DECIDE IF

something: by always returning SAY YES or SAY NO.

The something will usually include ARE, BE, CAN, COULD, DO, DOES,

IS, MAY, SHOULD, WAS, WILL, or WOULD. e.g.

To decide if a number is greater than another number:

If the first number is greater than the second number, say yes.

Say no.

Function: A routine that extracts, calculates, or otherwise

derives a value from a passed parameter. Function headers take this form:

TO PUT something's something INTO a temporary

variable:

Unlike procedures (which are called via imperative sentences) and deciders

(which are implicitly called in the condition part of IF statements), functions

are not usually called directly. Instead, the "something's something" is

used as if it was a field in a record. Like a "box's center", which you won't

find in the "box" record, because it is calculated by a function on demand.

Statements

From the instruction manual (see link below):

(1) I really only understand five kinds of sentences:

(a) type definitions, which always start with A, AN, or

SOME;

(b) global variable definitions, which always start with THE;

(c) routine headers, which always start with TO, which can

contain:

(d) conditional statements, which always start with IF; and

(e) imperative statements, which start with anything else.

(2) I treat as a name anything after A, AN,

ANOTHER, SOME, or THE, up to:

(a) any simple verb, like IS, ARE, CAN, or

DO, or

(b) any conjunction, like AND or OR, or

(c) any preposition, like OVER, UNDER, AROUND,

or THRU, or

(d) any literal, like 123 or "Hello, World!", or

(e) any punctuation mark.

(3) I consider almost all other words to be just words, except for:

(a) infix operators: PLUS, MINUS, TIMES, DIVIDED

BY and THEN;

(b) special definition words: CALLED and EQUAL; and

(c) reserved imperatives: LOOP, BREAK, EXIT,

REPEAT, and SAY.

See also:

P Sum said: ...my main objection is whether it really IS plain English. He gives the example "If the source is not colorized, put black into the color." I would have said "If the source is not colorized, make the color black." or "make it black" or "set it to black". Maybe with some additional natural language processing, it will be able to understand all of those, but for now, I suspect you are still really learning programming syntax that is camoflaged as language.

After all learning that you have to assign by saying "put the [x] into a/the [y]" is no different than learning that assignment is done by writing "y = x". Only the former is more familiar and perhaps likely to catch you out if you don't write exactly that and realise you can't use equivalent phrases in English such as "place the [x] in a/the [y]".